Our sustainability report is now live and free to download!

Airing Our Dirty Laundry

Airing Our Dirty Laundry

Sustainability

This week follows a historic weekend for OXWASH, in which we supported adventurer Tim Wiggins as he succeeded in kayaking around the Isle of Wight in record time, ably supported by our founder Kyle on the support boat. The ultimate aim of the endeavour is to raise awareness of microfibre pollution in the ocean. Tim towed a 0.5mm pore microfibre net behind his kayak and the support boat, which by the end of the journey had filtered a very tangible clump of these tiny particles out of the water. If Tim encountered this much plastic in 12 hours, how much will the average cod swallow before it ends up battered on your plate? We on this blog have already written about the scale of microfibre pollution in commercial laundry effluent, and the new OXWASH washing machines whose arrival next week we await with great anticipation will feature similar microfibre filters - although with an even finer mesh - to stop as much microfibre plastic as possible getting into the ocean in the first place.

This week follows a historic weekend for OXWASH, in which we supported adventurer Tim Wiggins as he succeeded in kayaking around the Isle of Wight in record time, ably supported by our founder Kyle on the support boat. The ultimate aim of the endeavour is to raise awareness of microfibre pollution in the ocean. Tim towed a 0.5mm pore microfibre net behind his kayak and the support boat, which by the end of the journey had filtered a very tangible clump of these tiny particles out of the water. If Tim encountered this much plastic in 12 hours, how much will the average cod swallow before it ends up battered on your plate? We on this blog have already written about the scale of microfibre pollution in commercial laundry effluent, and the new OXWASH washing machines whose arrival next week we await with great anticipation will feature similar microfibre filters - although with an even finer mesh - to stop as much microfibre plastic as possible getting into the ocean in the first place.

Learn more about Tim's work here!

In any discussion about taking measures to mitigate our impact on the environment, we think that examining our priorities, motivations, and decision-making processes is just as important as looking for technological solutions themselves. By way of illustration, consider the discussion currently taking place in many cities over the future of urban transport, exemplified in our case by last-mile delivery. In our beloved home city of Oxford, we feel most viscerally the insane congestion and pollution in the city centre, the threat to life posed by the city's inadequate cycling infrastructure and inattentive drivers, and the effects of inactivity on the population at large. It can be hard to see past these immediate concerns to the larger-scale environmental issues that would still be applicable if we operated in, say, Stevenage - a town with impressive segregated cycling infrastructure, but far higher rates of car use and no less susceptibility to the problems that climate change will bring. We need to look for the big picture and make sure that we have as positive a net impact as possible.

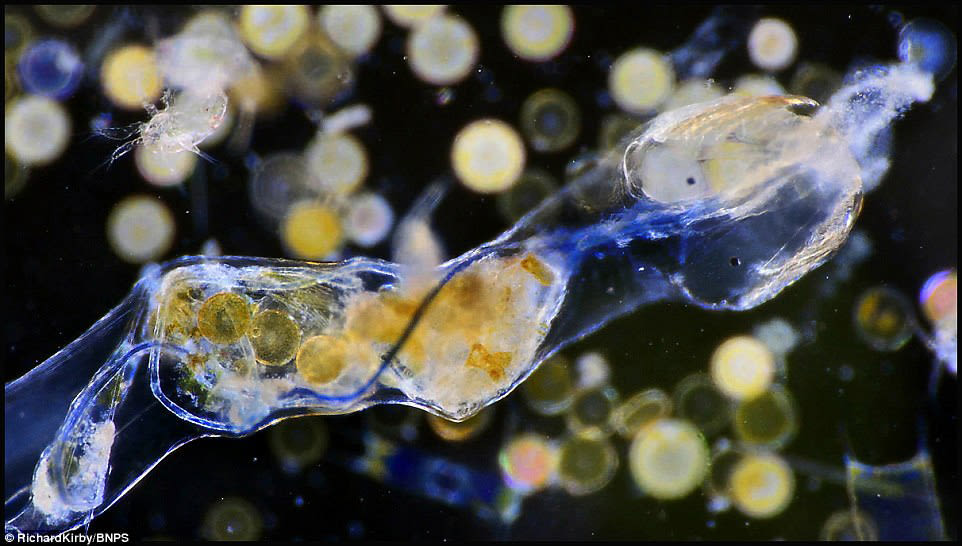

A zooplankton that has consumed a microscopic plastic fibre. Growing concerns about this issue have recently been voiced by papers including the Guardian (https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jun/20/microfibers-plastic-pollution-oceans-patagonia-synthetic-clothes-microbeads)

It can also be hard to be honest with ourselves about our achievements and challenges; we are rightly proud of our microfibre-filtration technology, biodegradable detergents, and compostable potato-starch suit bags, but this could easily overshadow the greater impact that making easy changes like switching to biodegradable laundry tags or washing at lower temperatures would have. This psychological effect is equally true on an individual scale; how many of us are fastidious about our kitchen recycling, yet give little thought to the environmental impact of washing our clothes? It's in focusing on the thoroughly unsexy problem of doing sustainable laundry that we think we have found not only a market niche but a consistent, effective and honest way of thinking.

In looking for solutions it is important not to lose a global perspective. We have addressed one criticism commonly levelled at electric vehicles - namely, that by adding another step to the energy cycle they are inefficient and merely outsource pollution to the fossil-fuel burning power stations that generate over half the UK's electricity - by powering our bikes, machines and office space with solar power. However, we must also face up to the environmental cost of the technologies that have made this possible. For example, a solar panel or lithium-ion battery may have to be used for several years before the emissions saved by the finished product offset the carbon footprint of the battery or panel's manufacture.

Furthermore, there is often a lack of clarity surrounding the conditions under which the finished product is made. Differing regulatory standards, inadequate third-party oversight, and an unwillingness on the part of producers to provide an honest assessment of their environmental footprint can render fruitless any attempt to find out, say, which toxic chemicals have been involved in the manufacture of a certain solar cell, or whether a battery uses Lithium that has been evaporated from brine pools in a country where water is scarce. This opacity will have to be addressed as the technologies we use become more commonplace and put more pressure on the supply chain.

Lithium brine evaporation pools, Atacama desert (Reuters)

The grave working conditions and human rights abuses endured by heavy metals miners in the DPRC and assembly-line workers in China have become well known in recent years, but how many of us have ever been able to trace the components of our smartphones to mines and factories operating under proper oversight and regulation? How many of us have even tried? How many of us - and I imagine that many reading this blog would say that they are actively concerned about environmental and human rights issues - have made a conscious decision to keep using our smartphones in the knowledge that they have probably not been ethically or sustainably manufactured, rather than choosing to duck the hard questions and forget where they come from?

We have made a start, but we believe that continuing to look for sustainability at all levels of the supply chain is crucial to making a real difference. Instead of merely outsourcing environmental problems to regions more remote in time and space, we must strive to tackle them wholesale.

Related Articles

B Corp™ certified.

Surpassing NHS-grade disinfection.